|

"Built almost

entirely with a labor force of over 1,000 slaves in July, 1864, the River

Line was a series

of connected Civil War fortifications intended to stop Sherman's attack on

Atlanta..."

Seventy odd years before the French even

dreamed of the Maginot Line, an equally impregnable version of that famous

defensive fortification was built in Cobb County. Both met the same fate -

out-flanked by the enemy.

Built almost entirely with a labor force of over 1,000 slaves in July,

1864, the River Line was a series of connected Civil War fortifications

intended to stop Sherman's attack on Atlanta.

The line was six miles long, extending from just south of Veterans

Memorial Highway (Bankhead Highway) into the community of Vinings. The

northern terminus of the fortifications was located at a point off Polo

Lane near the river, where a large artillery fort was constructed. The

line crossed Woodland Brook Drive near Polo Lane, Rebel Valley View,

Settlement Road, and the CSX Railroad (then Western & Atlantic), the line

of fortifications crossed Atlanta Road south of I-285. Then turning in a

more southernly direction, the line extended through Oakdale, and followed

the ridge on which Oakdale Road is located to a point south of Veterans

Memorial Highway, near Nickajack Creek.

In June and July of 1864, armies of the United States under Major General

William T. Sherman attacked Confederate fortifications on Kennesaw

Mountain. Confederate forces repulsed them in one of the bloodiest battles

of the war. Seeing the futility of continuing to attack a strongly

fortified line, the federals resorted to a flanking movement, the same

tactic which had pushed Joseph E. Johston's Confederate army of Tennessee

back steadily from Dalton to the outskirts of Atlanta.

Enjoying distinct superiority of numbers and equipment, Sherman

successfully used the tactic of confronting the Confederates with a

sizable force, while other units of his army moved around the side, or

flank of the rebel forces. In order to avoid an attack into their side and

rear, the southern forces would fall back and form a new line of defense.

After the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, this flanking movement began. Not

wanting to allow the federal forces to get between him and Atlanta,

Johnston once again withdrew, abandoning Kennesaw Mountain and its line of

fortifications.

On Johnston's staff was a brilliant officer with a variety of experience,

Brigadier General Francis Ashbury Shoup. In an effort to stop the pattern

of retreating, and to stop the federals short of Atlanta, Shoup conceived

the plan for a string of impregnable fortifications backing up to the

Chattahoochee River. He presented his plan to Johnston, and the plan was

approved in time to complete the fortifications before the rebel forces

fell back from Kennesaw through Marietta and Smyrna.

Shoup had spent a part of his life prior to the war in St. Augustine,

Florida, where he doubtlessly was inspired by the imposing Castillo de San

Margos. This old Spanish fort is a classic example of the use of bastions,

small arrowhead-shaped forts which protrude out from its corners. Gunners

in the bastions could fire into the sides and backs of enemies who may be

attacking another part of the walls. Likewise, fire from the walls would

protect the bastions. A graduate of West Point, Shoup was also well

educated in the design and use of military fortifications.

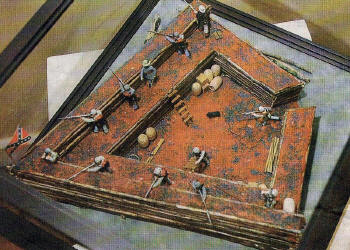

The Chattahoochee river line, sometimes called Johnston's River line,

consisted of 36 of these arrowhead-shaped forts, connected by a strong

wall of log palisades and trenches. The forts are commonly called "Shoupades"after

their designer, Gen. Shoup. Most of them were graded away as Vinings and

Oakdale developed, but a few still remain.

The most accessible, and the one most likely to be preserved, is near the

southern end of the line, and is on land now owned by Cobb County. Another

is on Oakdale Road, partly in an apartment complex, and partly in the yard

of a residence. One is off Atlanta Road in John Weilands's "Olde Ivy"

development. A few scattered Shoupades are in the yards of homeowners and

on church grounds.

Did the Chattahoochee River Line perform the task for which it was

designed and laboriously constructed? Obviously not, or the national

capital might be in Richmond today.

Confederate forces briefly occupied the River Line after their withdrawal

from Smyrna and Marietta. When federal forces, in hot pursuit, encountered

the line, bristling with cannons and Shoupades, they wisely decided not to

waste lives by throwing men against such an impregnable obstacle. Sherman

resorted to the same old tactic which had brought him from Dalton to the

edge of Atlanta, a flanking movement.

As soon as General Johnston heard that Sherman's troops has crossed the

Chattahoochee River above and below his fortress, he had his Confederate

army abandon the River Line and withdrew into fortifications around

Atlanta.

Just as German forces negated the power of the Maginot line by going

around it, so did the United States forces negate the effectiveness of the

Chattahoochee River Line.

Historians William R. Scaife and William E. Erquitt wrote a book on the

line in 1992, entitled the Chattahoochee River Line. The book contains

much more information, including photographs of model Shoupades, details

of construction, maps of the line and of troop movements, and more details

about the Civil War in Cobb County.

Originally published in April-May 2001

edition of Living Magazine by Marion Blackwell, reproduced with the

author's permission. |