|

Hunterstown:

North Cavalry Field of Gettysburg

By Troy Harman, National Park Ranger and Historian

Gettysburg National Parks Service

Hunterstown Cavalry Battlefield, also known as North Cavalry Field, is a

National Shrine waiting to be fully appreciated and brought into the fold

of sacred places visited regularly by patrons of Gettysburg National

Military Park. Fields and barns to either side of the

Hunterstown road,

just to the south of old town square mark the site of a significant

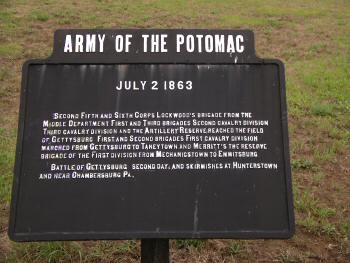

cavalry fight waged there after 4:00 PM on July 2, 1863. Union

participants involved were Michigan Troopers under Brigadier General

George Armstrong Custer versus the Confederacyís famous Cobbís Georgia

Legion, with support from Phillips Georgia Legion, the 2nd South Carolina

Cavalry and 1st North Carolina Cavalry. They were under the overall

direction of the capable Brigadier General Wade Hampton, who latter

replaced J.E.B. Stuart as Robert E. Leeís cavalry chieftain. Hunterstown road,

just to the south of old town square mark the site of a significant

cavalry fight waged there after 4:00 PM on July 2, 1863. Union

participants involved were Michigan Troopers under Brigadier General

George Armstrong Custer versus the Confederacyís famous Cobbís Georgia

Legion, with support from Phillips Georgia Legion, the 2nd South Carolina

Cavalry and 1st North Carolina Cavalry. They were under the overall

direction of the capable Brigadier General Wade Hampton, who latter

replaced J.E.B. Stuart as Robert E. Leeís cavalry chieftain.

Lines of battle were established a mile apart with Custerís men

establishing their artillery at Felty-Tate Ridge on the northern end, to

oppose Hamptonís rebel guns atop Brinkerhoffís Ridge directly south. In

the valley between, a fierce hand-to-hand fight would ensue across the J.G.

Gilbert and J. Felty Farms, intact to the present day. It began with

Custer ordering elements of the 6th and 7th Michigan cavalry to dismount

and move south on foot beyond and below the ridge, along both sides of the

Hunterstown Road. Concealed by fields carpeted with ripe golden wheat, the

Michigan troopers waded inconspicuously forward to the Felty Farm where

some of their best marksmen found excellent cover and elevated fields of

fire within the enormous Pennsylvania bank barn west of the road. Feltyís

barn was even large enough to conceal Lieutenant A.C.M. Penningtonís 2nd

U.S. Battery M, 250 yards to the north along the Felty-Tate ridge.

Meanwhile, to complete the deployment, dismounted men of the 7th Michigan

formed undetected in the tall wheat east of the Hunterstown Road, to form

a cross fire with the 6th Michigan.

Custer had arranged the perfect trap, but how to lure Confederate

cavalrymen into it required another step. To achieve this and complete the

perfect ambush, he would personally lead around sixty mounted men of

Company A, 6th Michigan on a daring charge toward the Confederate

position. Because the Hunterstown Road was tightly flanked on both sides

with post and rail fences, it was impossible for more than one company to

move at a gallop. Recognizing this, Custer would use Company A as a small

shock force to establish contact with southern troopers. After hitting

them hard to get their ire up, he retreated intentionally drawing them

back north to the prepared ambush waiting east and west of the Hunterstown

Road at Feltyís barn. Custer, a new brigadier nearly lost his life in the

initial charge in front of the Gilbert farm, where Confederates resisted.

If it had not been for Norville Churchillís timely rescue of Custer,

whisking him out of harmís way and onto his horse, later Indian Wars on

Western Plains may have taken on a different complexion.

In Kentucky Derby fashion, the horses of Cobbís Legion raced in the summer

air nose to tail with Company A, for a quarter mile up the narrow

Hunterstown Road, all-the-while bouncing between the fences which hemmed

them in like a bowling alley. So caught up in the chase were the

Georgians, that they fell like a hungry mouse right into the trap which

was released on them as soon as Union cavalry cleared the waiting

crossfire. Not being able to stop their horses in time, several

Confederates raced beyond the barn where Penningtonís artillery opened at

close range, killing five rebel officers. Between the two sides, eleven

officers were killed or wounded, indicating the short struggle was

vicious. Although statistics vary, the total losses at Hunterstown range

from eighty to one hundred men. Confederate survivors withdrew south down

the Hunterstown Road to the Gilbert Farm and subsequently Brinkerhoffís

Ridge. With both sides monitoring the other from a mileís distance, only

long range artillery was exchanged the rest of the evening. At 11:00 PM,

Judson Kilpatrick withdrew Custerís men and the rest of the division with

new orders to the Baltimore Pike.

The significance of this action far exceeds the fight itself, and the

ramifications were greater than many realize. The first of these has to do

with Culpís Hill being saved for the Union on July 2. When Custer enticed

Hamptonís Georgia and South Carolina Cavalrymen into a fight, he prevented

them from reaching the left flank of the Army of Northern Virginia by way

of the Hunterstown Road. Jeb Stuart had ordered them there to protect

Richard Ewellís left, while the latter assaulted Culpís Hill. When Stuart

learned of Union Cavalry at Hunterstown, he countermanded his original

order, to permit Hampton to stay and fight. Ewell has been criticized

greatly for not beginning his attack at Culpís Hill earlier on July 2, but

his delay in part was related to Hamptonís cavalry not arriving to protect

him from David Greggís division of Union cavalry sitting squarely on his

flank along the Hanover Road. To compensate, Ewell had to reassign 3,000

officers and infantrymen to the Hanover Road. This weakened his main

assault upon Culpís and Cemetery Hills. Indirectly then, the episode at

Hunterstown helped to save the Army of the Potomac's main position at

Gettysburg.

Another great consequence of Hunterstown is that Daniel Sickles Union

Third Corps, representing the left flank of that army near the Round Tops,

was largely unprotected by cavalry. Outside of one or two cavalry units

doing spot duty there, the Federal flank was vulnerable. This is so

because the Signal Station at Little Round Top incorrectly reported

between 1:30 PM and 1:45 PM on July 2, to have spotted a column of 10,000

Confederates with trains to be marching towards the extreme Union right.

What they actually saw was James Longstreetís countermarch moving

northeast before turning due south. Union Army Headquarters responded by

giving David Gregg orders to take some of his cavalry north from Hanover

Road towards Hunterstown and Heidlersburg to ascertain whether the large

Confederate column was coming through by way of modern Route 394 to

assault Culpís Hill and Meadeís lines of communication and supply below on

the Baltimore Pike. Judson Kilpatrickís Cavalry division was given this

assignment by Gregg. When Custer struck Hampton at Hunterstown, he was

actually trying to ascertain whether a column of 10,000 Confederate

Infantry lay beyond.

Had the Round Top Signal Station not crossed its signals, Kilpatrickís

division with Custer most likely would have moved to protect Sicklesí

left. Such a result should have erased the Meade-Sickles controversy,

because Kilpatrickís men naturally would have discovered, harassed, and

delayed Longstreetís men until Commanding Union General Meade rectified

Sicklesí line. Because Longstreetís Corps was without cavalry on July 2,

Sickles with Kilpatrickís help promised a decided advantage for the

federals on July 2. Circumstances in Hunterstown sidetracked this logical

scenario. There are many other historical points

to make about Hunterstown such as its early status as a rival with

Gettysburg for the county seat, a stopping point for President George

Washington during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1793, an important early

crossroads town, and site of a substantial Confederate hospital.

Regarding the hospital connection, the old town is still filled with the

charm of a late 1700ís hamlet, untouched thus far by modern development.

Quaint homes and settings undisturbed, harkening back to another time

include Kilpatrickís Headquarters at the Grass Hotel, the John Tate House,

Barn & Blacksmith Shop where George Washington shod his horseís shoes in

October 1793. One of the Tate sheds even bears artillery shell marks left

from the cavalry battle in 1863. The Great Conewago Presbyterian Church is

another impressive structure from the period, made of stone, and

documented as a Confederate Hospital. Each of these dwellings adds so much

to the historic time capsule that is Hunterstown, Pennsylvania.

With that said, every effort must be made to preserve the principle

battlefield at Hunterstown along with the charm and richness of the old

town sitting directly north of it. As development comes to Hunterstown, it

must tastefully build around the two and save both. Doing so is not only

imperative with respect to its National Register of Historic Places

status, but it is also wise. If developed right, all Hunterstown property

owners can boast a preserved national shrine in the heart of their town

that will only increase in monetary and cultural value.

Finally, as the July 3 cavalry fight, three miles east of Gettysburg, is

widely known today as East Cavalry Field; and as the ill-fated cavalry

charge led by Elon Farnsworth on July 3, two miles south of town, is

commonly called South Cavalry Field; so too should the Hunterstown clash,

only four miles north of Gettysburg be regarded as North Cavalry Field. In

this same vein, Bufordís cavalry fight one mile west of town on July 1

might be called West Cavalry Field. In all of these actions, Union cavalry

buffered key Union positions in four directions of the compass. Each site

is equally essential to accurately portraying Gettysburg as the most

famous battle for human freedom in American History. |